Clouds surround Edsel Ford’s legacy to automotive history. Not that it was locked away or hidden from view. It’s just that Edsel always stood in the shadow of his father’s stature and list of accomplishments.

Edsel Ford in 1921. photo courtesy Library of Congress

Henry Ford was a hard act to follow, and his lock on Ford legacy almost snuffed out any notice of Henry’s artistic, educated, and very sophisticated son Edsel. A son who was hooked on speedsterism…

Several quick facts about Edsel and speedsters:

• Edsel sketched speedsters as a child when he would go to the Ford plant after school.

• One of Edsel’s first cars as a teen was a cutdown speedster.

• The rights to use the “Mercury” name were purchased by Edsel for Ford Motor, according to noted Ford Model T historian Jarvis Erickson, after Edsel had bought a Mercury Speedster in 1922 for his personal use.

Mercury sport-body speedster ordered by Edsel Ford on Nov. 29, 1922 in Stutz Bear Cat Yellow. Edsel would later purchase the rights to use “Mercury,” a registered name, for Ford Motor. photo courtesy Jarvis Erickson collection

• Edsel’s fascination with speedsters no doubt informed his later design collaboration with E.T. Gregorie in making the Edsel Ford speedsters of the 1930s.

Formative Years

Edsel Ford was born in 1894 into a humble but close-knit Detroit family. Photos of him show that he was an active child; Edsel even had his own seat in his father’s experimental first car, the Quadricycle. During this period, Henry Ford held the position of chief engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit, but would soon move on to form the first of three automobile companies. Edsel’s mother, Clara, was a homemaker and Henry’s chief support in his endeavors. Edsel would be their only offspring.

Henry gave Edsel his own childhood workbench. And, although it is not recorded, Henry probably encouraged young Edsel to disassemble and study toys and machines. So it was likely that Edsel modeled his behavior after Henry’s as he lived a boy’s life of chores and explorations. This is borne out in young Edsel’s habits as he attended school, after which he would report to his father’s factory, do his homework, and interact with staff.

Memoirs and notes written by Ford Motor Company employees on file at the Benson Ford Research Center paint a picture of Edsel the student.

“[Edsel] was very much interested in the various types of roadsters and cars that appealed to him. He would make sketches and rough drawings of them and take them up and explain them to the people in the Experimental Department” (Memoirs, E.G. Leibold, General Secretary, Henry Ford Office)

Edsel impressed his elders with his artistic sensibility as it applied to automotive design:

“Edsel Ford wanted things that looked clever, looked fast, and were fast. He really had an eye for style. Everything had to be right…” (Memoirs, Harold Hicks, Engineer)

Edsel’s sketches in 1910, when he was 16, reflected the speedster cutdown style of the time.

Sketch of a cutdown speedster by Edsel Ford, 1910 illustration courtesy The Henry Ford

And in 1911 or 1912 Edsel designed a six-cylinder cutdown that Ford engineers constructed for him. What a life!

in 1912 Edsel designed this cutdown speedster. photo courtesy The Henry Ford

Despite being blessed with affluence, Edsel had been raised in a traditional family. Edsel had attended prep school at Hotchkiss in Connecticut but graduated from the Detroit University School in 1912. He eschewed college, choosing instead to work at Ford. Edsel was assigned to learn the daily management tasks of running the company, leaving Henry time to focus on engineering oversight.

President of Ford

Despite being opposite in character and leadership styles, Henry Ford appointed Edsel to be President of Ford Motor in 1919, a post that Edsel held until 1943. Although Henry retained an iron grip on the company and often conflicted with Edsel regarding products and direction, Edsel was still able to help Ford Motor thrive beyond the Model T, which lingered on as Ford’s only automobile until 1927.

Handing over the reins of Lincoln Motor to Edsel was important to both men, but Edsel’s contributions to Ford Motor were only just starting. He took the helm of the foundering Lincoln Motor Company in 1922 and turned it into a respectable Ford brand. He was directly responsible for the updated and wildly successful Ford Model A, which saved the Ford Motor Company from foundering during the Great Depression. Edsel initiated Ford’s first styling department, and his ideas inspired the Lincoln K-series, the Zephyr, and the Continental Mk 1, all of which are historically significant automotive masterpieces.

Edsel was not only a strategic leader who could inspire success in others, he had other talents as well. Edsel was a world class automobile stylist of the 1930s with an informed sense of engineering principles and practice. Edsel was an amateur artist, a patrician of Detroit art and culture, and a family man, sharing the parental responsibilities of rearing four children with his wife, Eleanor.

But he still had that speedster itch…

The Ford-Designed Speedsters

Edsel Ford would travel to continental Europe to observe, among other things, car design developments. Returning from one such trip in 1932, Ford met with his newly hired designer, E.T. “Bob” Gregorie, to propose constructing a speedster that reflected European styling. Ford would come to Gregorie’s project desk, where he had set up office at the Aircraft Division at the Ford Airport, and Ford would informally discuss ideas that he had while Gregorie sketched them out on a pad.

This informal process is how they conducted many of their design meetings. In 1985, Gregorie recalled that conversation with Ford from 1932 in an interview for the Design Oral History Project:

“Edsel Ford came to me and wanted a special body built on one of the first 1932 V-8 chassis, and I drew up a little boattail speedster with cycle fenders. A pretty little thing. We had it built practically in the Engineering Laboratory and over at the Lincoln plant.”

The car was aluminum-bodied and built on a standard Ford 106-inch wheelbase frame. Ford had told Gregorie to develop something that was “long, low, and rakish.” Although those words became the parameters for all of their collaborations on prototypes, the first example was hampered by using a stock frame, making the Model 18 Speedster short in length, tall in the saddle, and giving it a stubby appearance.

In 1932 Edsel Ford collaborated with his designer, E.T. Gregorie, to design this speedster on a Ford Model 18 chassis. photo courtesy The Henry Ford

Still, the speedster was a bit sporty, with a split windshield and a hood line that extended to the cowl to give it the appearance of greater length. Edsel Ford would keep the car at his estate, out of view from the prying eyes of his disapproving father, who reportedly butted heads with Edsel over most anything. This car would definitely have been a trigger!

Another trip to Europe inspired another special speedster in 1934. From this second collaboration between Gregorie and Edsel Ford, a much lower and sleeker design blended Art Deco principles with coachbuilding trends that Edsel had seen on Bugattis and Delehayes. This example clearly had Edsel’s sense of styling stamped on it.

The 1934 Model 40 Special Speedster was painted in Edsel’s favorite color, a Lincoln gun-metal gray, with gray leather interior. A Ford flathead V-8 powered the car. What distinguished the two-seat speedster was its hand-formed and welded aluminum body that was mounted on a beefed-up 113-inch chassis that was underslung at the rear, making it distinctly lower. The Aircraft Division’s artisans had put together a sleek street speedster that was not unlike current Indianapolis track racers.

This 1934 design by Ford and Gregorie, the Model 40 Speedster, represents a high point in their collaboration. photo courtesy The Henry Ford

Several aircraft design influences stood out, such as the large and elegantly arranged instrumentation, the machine-turned engine firewall, and the sculpted cycle fenders that were re-made from Ford Trimotor wheel fenders. The Brooklands-style split windscreens that sat atop the long hood completed the effect. All parts of the Model 40 spoke elegance; this car was Edsel Ford at his best!

The 1932 and 1934 prototypes were a culmination of Edsel’s ideas about speedsters, a fascination that began in his boyhood days, and these were cars that he drove regularly. What Edsel Ford found in his designer, E.T. Gregorie, was a kindred spirit who shared an appreciation for simple, unadorned lines that spoke speed. As Gregorie stated to Edsel Ford biographer Henry Dominguez,

“… the designs that we developed over the years were [Edsel’s] designs, not mine… in essence, I was able to put on paper and into clay the designs he was visualizing in his head.”

Edsel’s two models exemplified Art meeting Aerodynamics, as similarly-inspired speedster designs were flying off drawing boards all over the industry. Unfortunately, these two speedsters had to remain undercover in his estate garage, hidden from his father’s disapproval; there was never a chance that they could make production while Henry ruled Ford Motor Company.

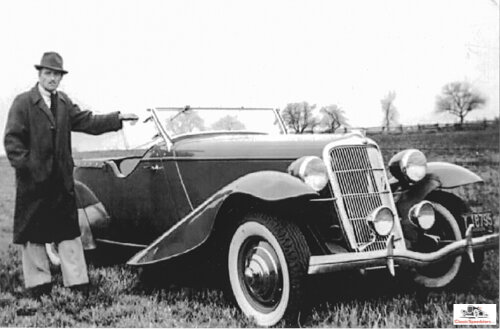

A third speedster prototype was developed in 1935 by Gregorie in collaboration with Edsel Ford by using a 1935 Ford chassis with its front axle moved forward 10 inches. A 2+2 phaeton-type body was made at the Ford aircraft division incorporating stock Ford roadster parts with some modification to make the prototype seen in the photograph. Its configuration resembles European car design of that period as seen in examples like the 1933 Alvis Speed 20, the 1934 Bentley 3.5 liter Vanden Plas Tourer, and the 1936 Hotchkiss Grand Sport.

1935 saw Ford and Gregorie’s last collaboration, a speedster phaeton prototype. Too bad it would never make it to market… photo courtesy Henry Dominguez collection

There would never be a market for this model at Ford Motor Company in America, and Gregorie’s attempts in 1935 to shop the prototype to stateside coachbuilders with which Lincoln had a professional relationship did not produce any results. In an article for a 1997 edition of Automobile Quarterly, Kit Foster wrote how Edsel’s ideas in the form of photos, drawings by E.T. Gregorie, and notes were eventually offered to some enterprising Brits in 1936, who in turn partnered with the Jensen brothers to purchase a steady supply of Ford V-8 chassis. Jensen Motors Ltd had already been producing their own sports car of a similar design, the 1935 Jensen-Ford Sports Special, using chassis supplied through Ford of Canada.

Although the 1935 Ford-Gregorie design dovetailed with what the Jensens had been doing since 1934, what chiefly transpired from theses negotiations was a much-needed contract that provided a steady supply of 1936 Model 48 (and eventually Model 68) Ford chassis and power trains to the Jensens. They in turn produced a Jensen-designed drophead 2+2 tourer and a closed saloon style until the onset of war hostilities in 1939. Edsel’s third speedster project may have inspired the Jensen sports tourer of 1936, but others in the UK and elsewhere were already producing cars with similar lines. The resemblance between the 1935 Ford speedster and the Jensen sports cars is clear, but a cause-effect connection is not.

The story of Edsel’s three speedster prototypes are covered in depth in Edsel Ford and E.T. Gregorie: The Remarkable Design Team and Their Classic Fords of the 1930s and 1940s, by Henry Dominguez. At the end of the design project for the third prototype speedster, Edsel Ford gave it to his chief designer and collaborator as a gift of appreciation. Gregorie subsequently used it as a daily driver, but later sold it to a friend. The car has long since disappeared: drawings, photographs, everything.

Gregorie with his 1935 prototype speedster phaeton, a gift from Edsel Ford for Gregorie’s design partnership. photo courtesy Henry Dominguez collection

Untimely End

Edsel would keep his first two speedster collaborations with Gregorie in his estate garage, and neighbors would see him drive his Model 40 in good weather. Driving this car was no doubt a respite from all of the responsibilities dogging his complicated life.

However, the daily pressures of running two car companies, the increasing involvement with defense production during World War II, and ongoing conflicts with his father all nagged at Edsel’s health. Despite a family bond and common automotive interests, Henry’s domineering nature, blinded by his own inflexibility, proved to be too much pressure, on top of everything else, for his son to endure.

Edsel developed chronic ulcers, suffered from undulant fever, and then, succumbed to stomach cancer at the age of 49 in 1943. Some believe that Edsel’s brucellosis infection resulted from unpasteurized milk served to him from Henry’s farm cows and hastened his demise, but this is just speculation.

What is clear is that Edsel Ford was a man who died well before his time. His three speedster collaborations with Gregorie, two of which he kept and drove regularly, showed Edsel Ford to be, at his core, an artist-enthusiast who remained true to his childhood dreams and sketches. Edsel possessed an authentic spirit, a boy-man who understood the worth of a sunny day and adventure in an unadorned, fast, open car.

Edsel Ford in his Ford speedster from 1912. photo courtesy The Henry Ford

This post is part of a series of mini-bios on noteworthy folks who owned and drove speedsters, and it is an excerpt from my upcoming book, “Classic Speedsters: The Cars, The Times, And The Characters Who Drove Them.” Thanks to the scholarship of noted Edsel Ford biographer, Henry Dominguez, as well as Model T historian, Jarvis Erickson, both of whom made this story possible. Illustrations and photographs from the Benson Ford library were used with permission.