Unsung Hero

The early years of the automotive industry in the Untied States witnessed innovation in almost every city and region. And in some cities, you could throw a stone in any direction and hit a building, inside of which was a car company in the making. It seemed like everyone was building an experimental car somewhere - everywhere.

New England was a hotbed of innovation since its colonial settlements formed into the six states that comprise it. The American industrial revolution hit there first: timber harvesting, coal excavation, iron foundries and steel-making, leather tanning and textile mills. New England had it all.

Steam-driven trains and watercraft were invented, developed, and then pushed out from New England, looking for new horizons. Populated with a highly skilled and motivated workforce, it was a natural that automobile manufacturing would find its way into the hustle and bustle of this region, beginning in the 1880s. Automobile companies like Stevens-Duryea, Stanley, and Pope would carve their names into the oak that was New England industry.

But did Metz? The company that produced over 42,000 vehicles during its tenure, far out-producing any of its competitors in the region? The car whose team won the 1913 Glidden Reliability Tour with a perfect score for all three of its cars. The company that hosted the Glidden silver trophy for a year?

1905 Glidden Trophy on display in AAA HQ. Originally it had a 1902 Napier perched on top of the globe; this was Charles Glidden’s car of choice when he had circumnavigated the world in 1902-03. The bust is solid silver. photo courtesy AAA

Metz was a car uncelebrated, a company forgotten in the mists of early twentieth century history. And its creator? A genius, largely unknown. And the reason for this post? Well, Metz and his company, Waltham Manufacturing, made an infamous speedster!

But first, the back-story on Charles Metz…

Metz the Bicyclist

Charles H. Metz was born of German heritage in Utica, New York in 1863. Apprenticed to his father as a carpenter, Metz also developed a keen interest in mechanical devices and high-wheeled bicycles. As a teen he sold Columbia bicycles in the Utica dealership and became a high-wheel competitive cyclist.

Metz’ problem-solving genius became apparent when he started creating accessories for bikes, and soon he was hired away by Union Cycle (near Newton, Massachusetts) to be its designer. During his short tenure there Metz worked on lightening bicycle weight and also secured 22 patents in his name.

1895 photo of Charles H. Metz photo courtesy AA magazine

In 1893 Metz struck out on his own and formed the Waltham Manufacturing Company in Waltham, Massachusetts to build “safety bikes.” The safety bike design that persists to this day had been invented around 1868, and by 1885 a bicycle craze was sweeping the country, as most everyone could now safely ride this contraption.

High-Wheel versus Safety Bikes diagram courtesy Wikicommons

This new sport coincided with the Good Roads Movement that eventually resulted in improved roads for all areas of the U.S. Bicycles were an important part of that movement. Safety bikes represented many things to people: fun, freedom, exploration, and even basic transportation. And good roads were sorely needed.

Metz designed the “Orient” bicycle, famous for a couple of reasons. First, Metz focused on lightness, and from that he developed a bike weighing only 20 pounds, half the weight of its contemporaries. Next, Metz hired a French bicycle racer and hot shoe named Albert Champion. Together they campaigned a racing Orient known as the “Mile-a-Minute” because of the velocity Champion achieved on the Waltham board track.

Waltham Manufacturing would produce and sell over 100,000 Orient bicycles during its career.

Relevant Digression

In addition to being a bicycle champ in France, Albert Champion was an entrepreneur himself, having patented his first spark plug in 1898. Champion spent his days with Metz developing and racing bikes, but sold plugs on the side. Although he became successful selling his Champion Spark Plug, his business partners pushed Champion out of his own company in 1908.

Down but not out, Albert then formed a rival firm, Champion Ignition Company, which made plugs for Billy Durant’s Buick Motor Company. This time Champion wisely trademarked them “AC Spark Plugs”, since he had “lost” his other brand name. Champion would be bought in 1908 by Durant for Durant’s General Motors Corporation. Ironically, Durant lost GM in 1910 to corporate shenanigans. Then he won it back in 1916. Then he lost it again in the 1920s...

Champion’s future, however, turned out better. His company was eventually made into a full division of the GM family in 1928. After several name changes, its current moniker has become “ACDelco.”

This old banner in Washington state is likely from the 1960s, before AC was merged into Delco of Rochester, NY. photo courtesy Wikicommons

Metz the Motorcyclist

Metz had already developed a tandem pacing bike which was designed to “break the wind” for racing bikes that would follow it on a track, thus allowing them to achieve higher velocities. Creative problem-solver that he was, Metz then developed the first American motorcycle in 1898. Known as the Orient Motor Pacer, it replaced the rider-driven pacer and developed higher speeds for the bikes following it. In the illustration, the rider in the rear monitored the engine.

1898 Orient Motor Pacer. The rider in back is purportedly Albert Champion. Waltham factory illustration

Waltham Manufacturing would continue to develop and produce motorcycles, a tricycle called an “Autogo,” and also four-wheeled runabouts, many springing forth from Charles Metz’ designs.

1902 Orient Motor Bicycle. Ad courtesy Horseless Carriage Foundation library

However, geniuses do not always live a calm and comfortable life. Following a heated dispute over the direction of his company in which his controlling partners were insisting on going into electric vehicles, Metz left the firm and went on a career walkabout that lasted several years.

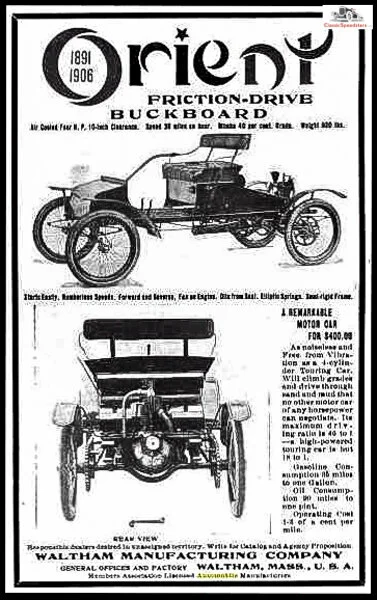

Waltham Manufacturing did not delve into electric vehicles after all, but instead produced the Orient Buckboard from 1903-1907.

1904 Orient Buckboard as it appeared in the 1904-06 Handbook of Gasoline Automobiles. Image courtesy AACA library

This ingenious and popular little wood-framed car became the U.S. Post Office’s first rural mail delivery vehicle in 1906. The Buckboard was made after Metz had left, so the design is not credited to him. Leonard Gaylor had been hired in 1902 as Waltham’s new designer, and a patent for the Buckboard was secured in his name. But, it does make you wonder…

1906 auto journal ad for the Orient Buckboard. Note that it used Metz’ friction drive. ad courtesy HCFI library

On his own, Charles Metz first dabbled with steam power, considered at that time to be a possibility; the Stanley brothers would become famous by producing a line of steam-driven cars. Metz then refocused and started producing motorcycles under his own name in 1902. His 80-lb racing motorcycle would be popular enough in 1903 to be adopted as the National Cycling Association’s designated race bike for that period; Metz wasn’t entirely flailing about in the wilderness.

By 1905 Metz bikes were using Thor engines as a cost-cutting measure. Thor is another famous early motorcycle name and very much sought after today. For instance, whenever Mike Wolff of History Channel’s American Pickers (TV series) comes across a Thor in someone’s grimy garage, he usually cackles with joy: “Hey, Frank! Come check this Thor out!” (Frank Fritz is Mike’s partner)

Despite this economic tactic of using ready-made engines, slow business times, probably brought on by the Panic of 1907, required Metz to merge with the Marsh brothers, who owned American Motor Company of Brockton, Mass. Together they produced the Marsh-Metz motorcycle for 1908.

1908 Marsh-Metz Motorcycle. illustration courtesy AA magazine

Metz the Automobilist

Always fascinated with things mechanical, especially with wheels under them, it was only a matter of time before Charles Metz was drawn into motorcars. Opportunity came knocking in 1908.

Waltham Manufacturing, which had been producing both the Orient and Waltham cars for sale but not having much of a go at it, was foundering under its debt load while weathering the mini-recession that had begun in 1907. The Waltham National Bank’s president, who had personally underwritten the mortgage on Waltham Manufacturing, asked Metz to reclaim the company and make it whole again.

Which Metz gladly did. And to accomplish this, Charles the problem-solver came up with an ingenious plan.

Next episode we will continue the with the story of the remarkable Metz car and its maker. Stay tuned, because the story gets even more fascinating!

Scholarship is important, but it would amount to nothing if not buttressed with solidly researched histories. I came across Daniel U. Holbrook’s 1986 well-written senior thesis on Metz, and it may have been submitted to Brandies University, which is situated in Waltham, Massachusetts. This led me to several articles in the Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal from 1909-1914, some of them ghost-written by Charles Metz, and then from there to three issues in the 1967 editions of Antique Automobile, written by a noted authority on the Metz. Without these sources this story would not have been possible; I am indebted.

Please subscribe to my journal if you haven’t yet! >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>> (box on right)

<<<<<<<<<<<<<<And use a social media link (symbol on left) to share it!