In our previous post, the story was told of two companies that made a speedster model in the 1950s. This episode continues that story and compares how they used their model to market, produce, and grow their companies. Lessons can be drawn from the outcomes that their separate efforts produced. Below, the story continues.

Success on the one hand…. and Failure on the other

Prior to the introduction of the 356 Speedster in 1954, Porsche had produced an aluminum-bodied predecessor, the America Roadster of 1952, a limited production model that perhaps tested the market for a more sporting version that might come later. Only 17 were produced by Heuer (Gläser-Karosserie) for the American market (16 in hand-formed aluminum, one in steel), and these were likely purchased by gentleman racers who knew the potential of a high-revving engine placed in an aluminum body with a trackside weight of only 1580 pounds! Retailing at over $4000, these were pricey… but very competitive on the postwar sports car tracks, and they no doubt brought attention to the brand.

1952 America Roadster. Note the attitude of the rear wheels and the curve in the door sill. photo courtesy Porsche Archives

Having fulfilled its purpose, the America Roadster experiment was discontinued after 1952, while Porsche carried on with the business of steel-bodied production cars. And Max Hoffman would have his lunch conversation with Ferry Porsche…

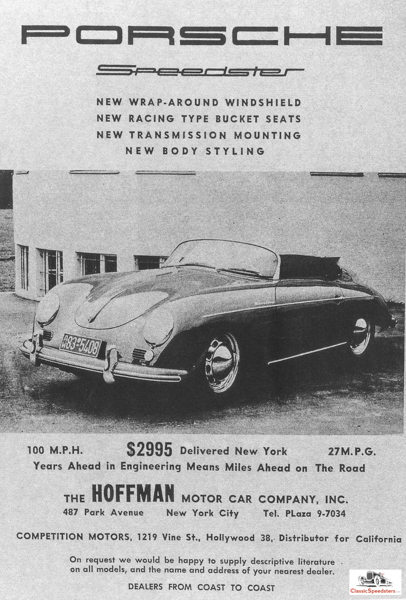

1954 356 Speedster. ad courtesy Porsche Archives

Following theses events, 356 Speedsters were introduced in 1954 and priced to tantalize an interested fan base; the showroom tag read $2995, a big drop from the America Roadster’s cost. And, as the name implied, the Speedster was a simple, no-frills open tub, meant to go fast and have fun and adventure. Side curtains, a skimpy top guaranteed to leak, an indifferent heater, and no radio. But fun? You betcha!

356 Speedster in its element - competition! photo courtesy Porsche Archives

Consisting of a steel unibody with an 82.7-inch wheelbase and overall length less than 153 inches, and weighing only 1750 pounds outfitted for the street, 356 Speedsters, affectionately known as “bathtubs,” were soon climbing the hills and clawing up the tracks, beating most anything and anyone who wanted to be first but were unfortunately not racing in a 356 Speedster. Which often meant that they were trailing behind one!

Hillclimb king… note the front wheels correcting for oversteer. Fun! photo courtesy Porsche Archives

Beginning in 1954, 356 Speedsters dominated their class so much that the Sports Car Club of America had to bump their classification from F-Production, (Triumphs, MGs, and the like, which were similar to Porsches in size and power) to E- and C-production (Corvettes, Jaguars, Ferraris, etc, which were bigger and more powerful). And still Porsche Speedsters were a force to be reckoned with, especially if the race had curves, a hill, or any race length over ten laps.

1955 lifestyles ad courtesy Porsche Archives

The marketing plan using the Speedster as a way to attract attention and sales for the more expensive coupes and cabriolets worked! The tried-and-true formula of “race on Sunday, sell on Monday” succeeded for this new entry to the U.S market. Porsche sales jumped from a measly 141 in 1952 to over 4000 in 1958, the year that the 356 Speedster was officially retired from production. Although Ferry Porsche had never really liked the Speedster, Porsche’s spartan sports car, it had established Porsche’s success in the U.S. market, thus fulfilling its purpose. And so he replaced it with a more staid but luxurious roadster version called the Convertible D for 1959. The D would last only one year, which Porsche supplanted with a roadster model for its B series from 1960-62.

No longer produced but not to be outdone, the 356 Speedster remained a terror in competitive circles even without factory support, spares, whatever, setting new records and achieving national championships well up into the 1980s, as seen in the ad below.

1989 ad celebrating the brand. poster courtesy Joseph Cogbill collection

To this day the 356 Speedster still competes in vintage racing events, but having achieved icon status, its greatest success is now found on the auction blocks, with collectors vying to own a piece of history.

And, as for Porsche… well, “the little tub that could” was no doubt the spark for Porsche’s early success in the market. Porsche today as a multi-billion Euro conglomerate bears little resemblance to its initial cottage-industry factory subsisting on Austrian schillings in a Gmund sawmill, but the original mandates of continuous improvement, design-to-win, and validate by racing remain guideposts for this historic automobile company. And lessons for others.

********************************

The usual turmoil of influence peddling within Studebaker, exacerbated in no small part by a merger with Packard in 1955, was accentuated with a board of directors whose shifting alliances allowed a classic conflict between engineering and design departments to continually simmer. To add to this confusion, Packard already had its own in-house design studio and was looking to terminate Loewy Associates as an unwanted expense. There were even mutinous elements within Loewy’s design team which influenced and eventually subverted the original concept of the 1953-1954 Starliner coupes.

Loewy’s last effort to increase sales and market share with his group’s coupe design from 1953 was to offer a sporty coupe for 1955, the President Speedster. Planted on a 120.5-inch wheelbase, with an overall length of almost 205 inches, and weighing in close to 3000 pounds, the President Speedster featured a 185-horsepower Passmaster V-8 and sported a dual exhaust, a dual or tricolor paint scheme incorporating colorful pastels, and a tachometer mounted on its engine-turned dash. The interiors were outfitted with diamond-patterned leather and vinyl. This was a snazzy car!

1955 Studebaker President Speedster factory image

A Los Angeles dealer offered a McCulloch supercharger as a factory-sanctioned option to boost performance, which it did. Tests showed that the standard President accelerated 0-60 13.4 seconds, the President Speedster in 10.3 seconds, and the supercharged version in 7.7! All featured a two-speed Studebaker Ultramatic transmission.

Magazines reported that the Speedster was fast, cornered well, and offered America a real five-passenger sports car. Loewy’s design group had been overruled by sales and marketing departments, and thus the Speedster was bedecked and loaded down with chrome, especially the front bumper, whose bulk looked more appropriate on a Packard sedan. But overall, the Speedster was still a sharp-looking sports coupe.

1955 Studebaker Speedster ad courtesy Studebaker National Museum

Production was limited to a disappointing run of 2215, and although Studebaker was back on track with over 133,000 in total sales for 1955, it could not break the vicious up-and-down market cycles that it found itself in. Loewy Associates were terminated, and so, with no champion to support it, the Studebaker Speedster became a one-year fling… with no effect on expanding the Studebaker customer base nor increasing sales.

After Loewy’s exit, Studebaker replaced the Speedster model with a sporty coupe called the Hawk for 1956, which continued through 1964. But repeated bad executive decisions, engineering and quality control issues, and having Ford and GM engage in a price war during the 1960s, all effectively spelled the end of Studebaker by 1966. In this market, no independent manufacturer could have survived, and indeed, they did not. Studebaker just happened to be another casualty of a war between giants.

Studebaker South Bend plant closes in December of 1963. Note the flag is at half mast. photo courtesy Studebaker National Museum

Lessons Learned

Both Porsche and Studebaker had started out as small family businesses with a dedicated team and a clear direction that listened to its customer base and offered the product and services that customers wanted. Not often easy in the tumultuous 20th century automobile business because the design-product implementation-sales (feedback) cycle often took 3-plus years for each new design. Porsche sidestepped that by creating one model, the Type 356, and basically sticking with that for 18 years, instead focusing on continuous and perpetual refinements.

Alliances and infighting are inevitable in any company that grows and succeeds. Politics and conflicts are part of the human condition. Studebaker was continually hobbled by cycles of bad executive decisions after going public in the 1920s, repeatedly beset with uncontrollable market forces, and felled by a price war in the 1960s. Some of its ideas were too soon for the markets, and in other cases, it ignored or abandoned its customer base. Ferry Porsche wisely removed his family’s direct control of Porsche in the 1970s and turned it over to professional executives to run. Strategic choices in leadership effectively kept the infighting manageable. Still, changing markets in the 1980s and ‘90s almost tanked the company twice, but bending to the winds of change and attending to the wants and needs of customers has saved Porsche time and again. The latest example is the growth of SUVs at Porsche, whose customers wanted more than just sports cars in the Porsche lineup. Porsche listened; Porsche responded. Porsche thrives.

1932 Indy 500 with Studebaker 5-car team. photo courtesy Studebaker National Museum

Studebaker dallied with endurance records and, to a limited extent, track racing in the 1920s and 1930s. Had it stayed the course with competitive activities, even adding a speedster in the mix every now and then, perhaps its future may have changed for the better. Porsche had racing in its blood since its beginning, and to this day competition is a fundamental, factory-supported company element. Racing is an expensive business, but it does expose the product to the public, helps refine and improve components, and it does speed up the innovation process that continues to this day. Certainly Porsche stands tall in this respect, and racing has made all the difference regarding its continued corporate presence.

Do speedsters have a place in a model lineup, and do they make a difference? Yes, but only if they are used wisely. Studebaker’s Speedster was a glam job, a dressed-up President Coupe rolled out with no plan for competition or continuation, something thrown against the wall to see if it would stick. Which it didn’t. Porsche’s 356 Speedster was a marketing bet made by Max Hoffman that exploded Porsche’s market exposure for the U.S. market. And it was backed up by racing success for years to come, adopted by Hollywood as a stage set piece to add “cool” to any movie scene, and it achieved icon status among sports car aficionados.

To this day, Studebaker retains a solid following of true believers who express admiration and support for a car that should have continued but did not. On the other hand, Porsche has motored on into the 21st century. Its 356 successor, the Type 901, was introduced in 1965. It is still being produced (as the 911) and continuously improved upon. Porsche remains one of the best sports cars in the world.

And, of course, Porsche still produces a Speedster… a 911 Speedster!

2018 Porsche 911 Speedster photo courtesy Porsche AG

Special thanks go out to Tobias Mauler of the Porsche Archives for his help in gathering historic Porsche photographs for this piece.

Next post: Who drove speedsters? We will periodically write about a person who owned or drove a speedster to look at the personalities behind the wheel of these fantastic cars. Some were well-known, some were unknown. We’ll read about one in our next episode.