Although I covered the Mercer dynasty as a chapter in my book, Classic Speedsters, the company deserves a mention in my blog as well because of its fundamental influence on the growth and acceptance of the speedster in American lives. By 1910, several car companies had already been marketing sport models, making the 1910 Mercer Model 30 Speedster a Johnny-come-lately. But no other name would rise to the top of the bottle like fresh cream as quickly as did Mercer’s later Raceabouts.

Hands down, The Mercer Raceabout was that good of a speedster!

Opportunity Knocks

The Roeblings and the Kusers of Mercer County, New Jersey were entrepreneurial families with a range of products that they had developed and sold through their successful businesses.

John A. Roebling, best known for constructing the Brooklyn Bridge, passed his ideas and work ethic on to his children, who in turn would complete the bridge project and start the John A. Roebling Sons Steel Company, which made stranded steel wire. They also founded the town known as Roebling, New Jersey.

The four sons of Swiss engineer and emigrant Rudolf Kuser were a bit more divergent in their endeavors, managing gas, electric, and streetcarcompanies. One son supervised firms that supplied nearby hotels and restaurants with ice and beer. By 1900 the Kuser sons were established and quite successful.

In fact, both the Roebling and Kuser families were prominent capitalistic forces in their communities who had developed opportunities that had come their way and had prospered from sheer hard work. They also invested in other companies of interest to them. For instance, the Roeblings and Kusers backed William Walter’s venture in automobile-making. William Walter was a New York chocolatier who had also dabbled in automobile-making, and he had produced a high-quality touring car known as the Walter.

The Kusers offered Walter factory space in New Jersey, and so Walter moved his operation, then known as the Commercial Car Company, from New York City to New Jersey. It would later known as the Walter Automobile Company.

1907 Walter Automobile ad. This was a high-end vehicle of the period, but unfortunately, it was produced during the Panic of 1907.

As investors, the Roeblings and Kusers must have known that Walter was struggling as a carmaker, and this may have inspired them to form a car company of their own, which they incorporated as the Mercer Motor Car Company. So when the Panic of 1907 hindered, and then halted, Walter’s ability to maintain his debts, Walter defaulted on a bond payment in 1908, and foreclosure followed soon thereafter. During foreclosure proceedings, the Roeblings and Kusers swept in and bought the Walter Company’s assets and folded them into the Mercer company.

Turmoil and Change

Meanwhile, a prototype speedster that was known as the Roebling-Planche had been developed by Walter, and its development continued with the new company. Its beast of an engine was designed by Etienne Planche, displaced 1039 cubic inches, and it produced between 120 and 140 horsepower for its 115-inch wheelbase frame. True to form, this rip-snorting speedster was capable of well over 100 miles per hour, quite the feat for 1908! Although three were built, they remained a prototype that would not go into production, as Planche would soon leave for other work opportunities.

1909 Roebling-Planche ad.

While employed as chief engineer at Walter, Planche had also freelanced other projects on his own time, designing a four-cylinder motorcycle engine that the Motor Car Specialty Company of Trenton had commissioned in 1908. Another commissioned project was the Sharp-Arrow Speedabout, produced in 1909 for William H. Sharp, a local photographer and race driver who campaigned his Speedabout for two seasons until succumbing to a racing accident in 1910. The Sharp Arrow’s story is covered in blog post 59.

The year 1909 was a turning point for several individuals at the former Walter factory. Planche left to design for Louis Chevrolet, and Finley Robertson Porter was hired to replace him. William Walter returned to chocolate-making in New York City. As all of these events panned out, the new Mercer Automobile Company emerged as the gold.

Seemed like a Good Idea

The Mercer Automobile Company initially focused on producing a moderately priced car to broaden its appeal and customer base. Although staffed with engineers, Charles G. Roebling and his son Washington II (“Washy”) headed product development. And like his friend William Sharp, Washy was into speedsters.

Washington Roebling II. image courtesy Wikipedia

Washy had co-developed a prototype Mercer Model 30 Speedster using an unnamed ready-made powerplant, perhaps a Planche-designed engine as with the Sharp Arrow—who knows? However, with this engine the speedster won two time-trial sprints, a one-kilometer and a one-miler, at the 1908 Labor Day Races in Spring Lake, New Jersey. The prototype then grabbed a first-place trophy at the 1909 Delaware Valley Auto Club road rally. To confirm that it was also race-worthy, Washy entered the 1910 Savannah International “Light Car” race and scored a second–place finish. Ironically, it was at this same road race that William Sharp fatally crashed his Speedabout. Having witnessed this unhappy event, Washington would subsequently retire from racing.

1909 Sharp Arrow w Sharp brothers, from the Sharp Arrow sales brochure.

The production version of the Mercer Model 30 of 1910 housed a much tamer 279-cubic-inch Beaver-built engine.

1909-10 Beaver engine. image courtesy reader Mike Hopkins

Its 4.375” x 4.75” bore and stroke L-head (valves on one side) four-cylinder produced 34 horsepower at 1700 rpm through a three-speed transmission, and it rolled on a 116-inch wheelbase. Three models were offered: a five-passenger Touring Car, a four-passenger Toy Tonneau, and a Speedster.

1910 Model 30 Speedster from the Mercer sales brochure. image courtesy AACA library

The Speedster was attractively priced at $1950 F.O.B. and the engine size qualified it for Light Car events, which limited displacement to 300 cubic inches.

Mercer Model 30 chassis from the Mercer brochure.

The Speedster’s chassis, rounded radiator, and cowl resembled the Planche-designed Sharp-Arrow and looked all the money. The Speedster was advertised in its catalog as “a two-passenger car which appeals to a man wishing a fast, powerful, racy-appearing car” and was offered in a racy blue or green. However, its high stance and its underpowered Beaver engine made it ungainly and slow. It was essentially a street speedster and would not be suitable for track work.

Total Mercer production for 1910 was 791 units, a handsome number for Mercer’s first year. Actual production records are scarce, but most experts agree that during its 16 years of manufacture (1910-1925), Mercer’s output summed to little more than 5000 cars. Mercers were hand-assembled, which ensured their quality but which also limited output.

Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

Although no longer racing, Washington Roebling II continued Mercer product improvement. Finley Porter had been recruited in 1910 to replace the departing Planche, and Roebling and Porter quickly developed Mercer’s most noteworthy and memorable vehicle, the Type 35-R, which rolled out mid-1910 as a 1911 model.

1912 Mercer Runabout. Note its use of doors. catalog image courtesy AACA library

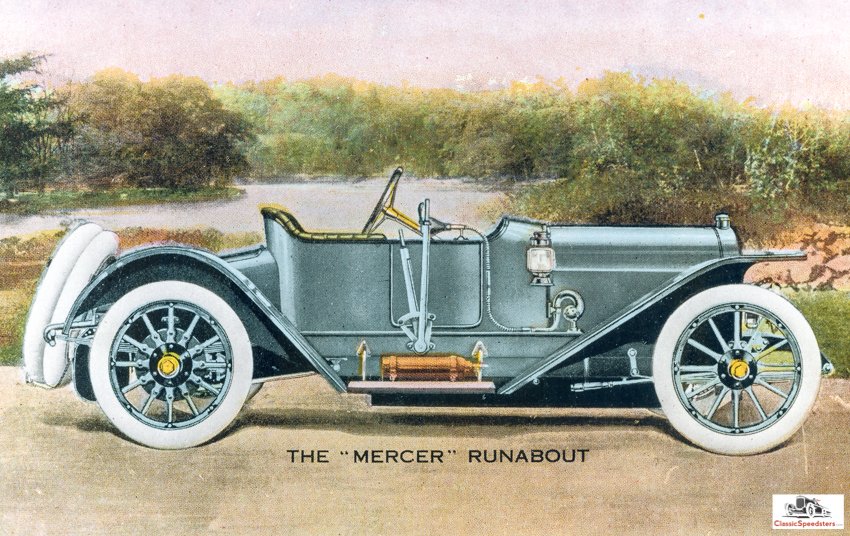

Two versions of Mercer’s early sports models were produced. The Runabout, which was introduced for 1912, featured a low-slung, rounded cowl, a semi-enclosed passenger compartment, and a 25-gallon barrel tank mounted behind two bucket seats.

1911 Mercer Raceabout. image courtesy AACA Library

The Raceabout version, which had preceded the Runabout by a season, differed notably with a leather strap securing the cowl, no passenger enclosure, and lowered bucket seats squatting on an open platform in classic speedster style. The Raceabout looked every bit the hairy beast that it was, hunkered lower than its competitors, and was good for 75 miles per hour if the roads would allow it!

The Type 35-R Raceabout represented the Mercer auto at its best. Unfettered by committees and focus group opinions, Roebling and Porter created what could be America’s first muscle car, as the Raceabout was completely purpose-built for speed. Not only did they design the Raceabout, they put together a team of racers that Porter would supervise as part of his role at Mercer. From the 35-R, they developed the track-purposed Model 45 Racer (more about this in the next episode).

1911-12 Mercer Type 35 engine. brochure image courtesy HCFI library

The four-cylinder T-head engine that Finley R. Porter designed for the Type 35 versions for 1911-1914 used an aluminum crankcase supporting two sets of paired cylinders machined to an .001-inch tolerance. The pistons were gray iron, mounted on forged steel connecting rods that rode on a forged steel crankshaft. Everything was dynamically balanced to avoid destructive resonant vibrations; Mercer prided itself on smooth running. A Bosch magneto supplied the spark to each cylinder, fired by twin plugs, and a Fletcher carburetor fed the beast, whose 4 3/8-inch bore by 5-inch stroke pumped out 58 horsepower at 1800 rpm.

The Type 35 was an artisan-built speedster whose durability at the tracks and longevity of its racing career testifies just how well-made this car was. It was framed in channel steel, narrowed at the front for turning radius and kicked up at the rear to keep its body low. The wheelbases for the two-passenger Runabout and Raceabout cars were set at 108 inches, seven inches shorter than the Model 30 Speedster had been.

The Raceabout did not use a battery or starter, which shaved off a hundredweight. At 2450 pounds fighting trim, this production speedster could allow its owner to motor directly from the showroom to win at the track, be honored on the podium, and also speed home in time for dinner!

The Type 35 racing version, stripped of street attire, dominated from go, winning five major races out of six in 1911. Ralph DePalma set eight new class speed records at the Los Angeles Speedway in 1912. Mercer’s ability to win attracted other notable drivers such as Barney Oldfield, Charles Bigelow, Spencer Wishart, Hughie Hughes, and Caleb Bragg. Together or individually they battled for glory on tracks and courses such as Elgin, Santa Monica, Brighton Beach, and Fairmount Park. (Img 11 Type 35 Raceabout at Elgin ad)

1912 was also notable for the unexpected departure of a company leader. Washington Roebling II, one of Mercer’s chief driving forces, sailed with the Titanic on its maiden voyage from Europe and, as tragically reported, on into history. Heroically Washington Roebling II would surrender his lifeboat seat to save women and children, but at the cost of his life.

This theme of moving ahead, only to be knocked back by unforeseen forces, would repeatedly hound Mercer Automobile and hinder its fortunes until Mercer’s eventual demise. We’ll cover more of Mercer’s racing achievements in the next episode.

1911 Mercer brochure cover. image courtesy Tim Kuser collection

***************************

This blog piece about Mercer is excerpted from my book, Classic Speedsters. If you have not yet purchased a copy for yourself, I encourage you to do so with all due haste. It’s convenient to read blogs online, but there is nothing quite like holding a book in your lap with a cup of something close by. Reading a physical book is an experience that cannot be matched by any electronic device, and my book is an excellent example of that very experience that will reward you for years to come. You can get yourself a copy from my website, https://ClassicSpeedsters.com.

Classic Speedsters—the book

In the near future I am going to produce a newsletter of things that are happening in my writing world that I’d like to share with all of you. As a reader of my blog, you are automatically opted in, and of course there will be an opt-out link if you choose to do so. I hope that you don’t; you won’t be disappointed.

So, in the meantime, go out and drive that speedster!

WOW!