In the previous episode we covered Ab Jenkins’ early life and how his reputation for speed and endurance brought him sponsorships and rides. Jenkins record-setting forays in cars brought him to the peak of his career as the man to beat on the salt flats of Utah. And, during all of this, he continued to encourage other land speed racers to come to Bonneville and try their luck.

Jenkins and Duesenberg Dominance

Despite the Depression years, 1933 was the beginning of fierce competition in ultimate speed. Ab Jenkins finally convinced his British contemporaries, Sir Malcolm Campbell, John Cobb, and Captain George Eyston, to consider Bonneville over Daytona, which was limited by its geography, being a dangerously narrow and relatively unstable twenty mile sand strip bounded by the ocean. In contrast, Bonneville offered a three-mile wide by 13-mile long expanse of hard-packed salt.

Ab Jenkins setting speed & endurance records for Auburn, 1935. Shipler photo collection, courtesy Marriott Library, U of Utah

Jenkins, who was now a test driver for Auburn, had set a Class B (for stock car) speed record and an endurance record at Bonneville in a 1935 Auburn 851 Speedster. Shortly after this event, Auburn president Roy Faulkner and offered a Duesenberg chassis and the services of Augie Duesenberg’s race shop across from the factory to contest a Duesenberg in Class B on the salt flats.

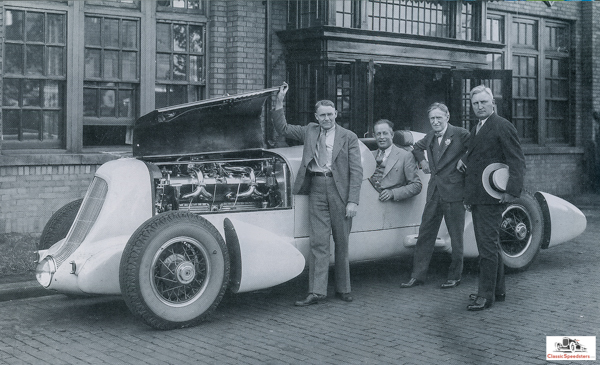

1935 Duesenberg Special. Seated is Jenkins, with designer Augie Duesenberg standing at left and Harvey Firestone at right. photo from Jenkins Family Collection, courtesy Gordon Eliot White

Duesenberg’s J. Herbert Newport cloaked the 142.5” SJ frame with an elongated speedster body, and Augie, along with cam specialist Ed Winfield, worked their magic on the supercharged SJ engine to ensure that it developed every bit of 400 hp at 5000 rpm. A spare engine was prepared, which was good, because on the first attempt, while challenging all of John Cobb’s speed records, the Duesenberg Special spun an engine bearing and Jenkins had to quit the run.

On the second attempt, the crankcase split. Swapping engines, Jenkins enlisted Tony Gulotta, an Indy 500 racer and friend, as his relief driver for a third try. Despite a fire in the cockpit caused by a loose cable, luck held and the Duesenberg Special established a new series of records for Class B, including a 24-hour endurance mark covering 3,253 miles at an average speed of 135.470 mph. A 25-minute filmed re-enactment of the Auburn and Duesenberg runs are featured in a King Rose Archives short that can be viewed at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kc0AzBC8Mmg

Only days later, on September 3, 1935, the absolute speed record fell to Sir Malcolm Campbell, who set a new world’s record of 301.337 mph in the Bluebird, his custom land speed racer. A short time after that, Captain Eyston bested Jenkins’ new record by setting a new 24-hour record of 140.520 mph in Class B with his Rolls-Royce Speed of the Wind.

Swapping speed records between these individuals would continue for some time. In 1936 Jenkins returned to the salt flats with his Duesenberg speedster which he had since purchased from Auburn, and a naming contest sponsored by the Deseret Daily News had rebadged the speedster to be known thenceforth as The Mormon Meteor. Into the Duesenberg chassis Augie had stuffed a 1750 cubic inch Lycoming-made Curtiss V-12 that produced 750 hp, and this, along with other changes, resulted in the designation Mormon Meteor II. Relying on Indy 500 veteran Babe Stapp, the pair set new International Class B records for everything from 50 miles on up to 24 hours (153.823 mph) and 48 hours (148.641 mph). Despite all of the competition, the end of the season saw the Mormon Meteor II still king of the salt flats.

1936 Mormon Meteor II with Augie Duesenberg at left, Jenkins at right. Shipler photo collection courtesy Marriott Library, U of Utah

After a bad weather season had shortened the 1938 racing schedule on the salt, and after handling issues caused by the big Curtiss engine came to light, Augie Duesenberg realized that the existing Duesenberg chassis was past its limit. He then designed a longer and stronger custom chassis that also had room for two engines, but the rest of 1938 turned out to be a washout on the flats, so it was not run.

In 1939 Jenkins returned to Bonneville with the Mormon Meteor III. Jenkins hired Hollywood stuntman and Indy 500 driver Cliff Bergere, himself a Duesenberg SJ Speedster owner, and the two competed against the best that the British could offer until World War II in Europe curtailed British involvement.

Just before hostilities shut down the salt flats in 1941 for the war’s duration, Jenkins and Bergere set new records in American Class A and World Unlimited category from 50 km to 24 hours. After the war, the Mormon Meteor III would continue to set speed records until its retirement in 1950, becoming one of the most significant American land speed racers to ever cross the salt.

Mormon Meteor III in 1950. Note the elongated frame. Shipler photo collection courtesy Marriott Library, U of Utah

Jenkins’ vision for the salt flats, as well as the speed records that he and others obtained there, put Bonneville on the map as the place to go for world class speed. Bonneville maintains that distinction to this day.

Fade to Black

Jenkins, Utah born-and-bred, was so popular in his home county that he was drafted to be mayor of Salt Lake City in 1940 without even making a speech or spending a cent on campaigning. After serving one term, Jenkins retired to volunteer in public service roles, especially as an advocate for road and driver safety.

In 1956, at the age of 72, Jenkins came out of retirement to partner with his son Marvin Jenkins and once more set speed records on the salt, but this time in a Pontiac coupe, achieving a stock car record average of 118.375 mph for 24 hours.

In 1956 Ab & Marvin co-drive to set speed & endurance records for an upcoming Pontiac coupe. photo Jenkins family collection, courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Soon after this event, Jenkins died of a heart attack on August 9 after attending a baseball game with General Motors officials in Milwaukee. Harley Earl, chief designer for GM, had designated the new Pontiac for 1957 to be The Bonneville. Ironically, this would honor Jenkins’ last record-setting feat, a fitting tribute to a go-fast speedster fanatic!

The Duesenberg Special at the Amelia Island Concours, 2011. photo copyright 2011 Ronald D. Sieber

Many thanks to the Utah State Historical Society and Utah State University library resources that helped make this possible, as well as support from author Gordon Elliot White. For a closer look at Ab Jenkins, check out these books:

· Ab & Marvin Jenkins: The Studebaker Connection and the Mormon Meteors, by Gordon Eliot White

· The Salt of the Earth, by Ab Jenkins and Wendell J. Ashton (out of print but available)