Begin at the Beginning

Automobile companies of the nineteen-teens were still developing methods and infrastructure to work themselves out of the garages and small shops in which most had originated back in the 1890s. Henry Ford had built his Quadricycle in a small shed out back in 1896. He then had to remove a doorway to get it out! Edgar and Elmer Apperson had to create a car from a Sintz engine that Elwood Haynes had summarily dropped off at the Apperson garage in 1893.

These folks and many others had an idea, a goal to make something new and radical, and a tankful of moxie to get ‘er done.

Automobile firms and dynasties rose from these early and humble roots.

Kissel Kickoff

William and George Kissel had learned well at the feet of their father, a German immigrant who had moved his family into Hartford, Wisconsin to start a farm implements business. William and George created the Kissel Motor Car Company in 1906 with the support of two other brothers and backing from their father. To start off, the brothers built a prototype with their workmate, Sam Toles, to whom they would gift their first car as the company got off the ground.

1906 Kissel working prototype. Image courtesy Wisconsin Automotive Museum.

The initial Kissel automobiles were assembled with outsourced components until sales success afforded them the opportunity to make their own parts and assemblies, which transformed their business model and would inform their work culture.

Kissels were built by hand to a very high standard of quality “in the German tradition”, aided by hiring gifted engineering talent imported from Germany. “Kissel Custom Built” was their advertising slogan and core belief. As touted in Kissel sales brochures, their cars were made

as if to individual order, under one roof, where uniformly high standards of workmanship govern every detail of design and construction.

This was the Kissel mandate: build or rework everything that went into their cars to meet their very own stiff requirements. And what they produced were magnificently hand-built beauties for an affluent middle class market.

Kissel engines being assembled, one tech per engine assembly. Image courtesy Wisconsin Automotive Museum.

It’s Nice That We’re Having Weather

Automobiles of this early era were universally topless until manufacturers could develop the tooling necessary to create a true hardtop in steel; this didn’t occur until the 1930s, when steel manufacturers started to create roll steel wide enough to fabricate roofs. Until then, the solutions that came forth were mostly in canvas and wood.

Brave soul, eh? Image courtesy Wisconsin Automotive Museum.

Kissel developed what would be touted as the “All-Weather” top in 1914 to address the challenges of their climate. After all, this was Wisconsin!

However, that solution was focused on their bread-and-butter lines: the sedans, touring cars and limousines, the cabriolets. Speedsters? Nah….

1916 ad for the All-Year removable top, which could be stored at home or by the dealer. Image courtesy AACA library.

It wasn’t until the second generation of the Kissel Speedsters that a viable solution for them would emerge.

The Kissel Enclosed Speedster

The Enclosed Speedster was an outgrowth of Kissel’s philosophy of continuous improvement of their “Kissel Custom-Built” generation of cars, roughly 1918-1927. The Enclosed Speedster of 1926-1927 came with a six cylinder producing 61 horsepower for its Models 55 Standard and DeLuxe, or its eight cylinder Models 75 Standard and Deluxe.

1925 Kissel 6-55 engine. Image courtesy AACA library.

1925 Kissel 8-75 engine. Image courtesy AACA library.

Overall, it was a handsome car that was a lighter and more powerful sibling to the other models offered by Kissel. For 1928, the hardtop coupe-roadster would henceforth take over that role.

1927 Kissel Enclosed Speedster. Image courtesy AACA library.

(editor’s note: more history of Kissel can be found in my previous article titled Amelia Earhart and her Kissel Gold Bug Speedster, May 24, 2019. See article index for that link.)

Franklin Steps In

Like many auto manufacturers, the H.H. Franklin Manufacturing Company started out in 1902 in Syracuse, New York with an air-cooled engines solution for their propulsion system.

1910 Franklin 6-cylinder engine. Note the barrel shaped engine cowl, which resembled a 55-gallon drum on its side. The air box around the cylinder fins guided the air blown in by the flywheel-mounted fan at left; the air would exit vertically into the engine cowling. Image courtesy H.H. Franklin Club library.

Air-cooled required no coolant to run; they did not freeze up in winter and crack their blocks; they were simpler in design and often lighter and cheaper to build. These were all important considerations in upstate Syracuse, New York, a location used to lake-effect this or that from nearby Lake Ontario just about every day of the year. Snow was not uncommon as early as October and as late as May.

In fact, air-cooled engines were standard practice for several for auto companies such as Porsche until 2000, when emissions legislation and noise strictures effectively killed the air-cooled engine for use in motor vehicles. A pity…

Franklins had a number of innovative solutions in their cars that carried with the line while John Wilkinson was their chief engineer. They had a completely wooden frame (it flexed with the bumps in the road); they had full elliptic springs, which allowed tires to last up to 20,00 miles (unheard of then for all other cars); the engines had overhead valves; and, of course, they had air cooling.

Franklins had a variety of hood shapes—a Renault-style sloping hood, a 55-gallon drum-shaped hood, something that looked like a waffle iron, and finally the horse-collar hood—all shapes the Wilkinson had designed and mandated. Eventually Franklin dealers in 1923 revolted and demanded a radiator and hood style to resemble what everyone else was selling. They argued: “Who cares if it’s a false radiator—at least it isn’t butt-ugly like the Franklin designs!”

H.H. acceded to the dealers, as he wanted to sell cars. However, this was too much for Wilkinson and his ego; he immediately resigned and went off to create his own car. Which, incidentally, failed…

Franklin Steps Up

H.H., as he was known around his factory, then hired outside help for improving the Franklin bodies, and J. Frank deCausse was among the first to design for Franklin. DeCausse created a very classy and trend-setting speedster for the company in 1926, and we’ll cover that in another post. However, here’s a glimpse:

1927 deCausse Sport Runabout. Note the sharp vertical sides that come to a boat tail, a design innovation developed by deCausse. Image courtesy H.H. Franklin Club library.

In 1928 Raymond Dietrich was hired to design for Franklin, and an ironic coincidence of events came together to help him bring a remarkable speedster with a hardtop to market.

In 1927, Charles Lindbergh had flown the Atlantic Ocean by himself and had set the world of aviation on fire. This singular event also electrified the automotive design world, which in turn adopted aero design as a trendy new theme that would manifest itself in designs from 1928-1958. Quite the run!

In 1928, Charles Leininger of the United States Advertising Company was hired to promote the new line of Franklins, and he created the Franklin “Airman” series to ride the wave of interest in all things aeronautical that was sweeping the United States and the world beyond. In addition, Leininger had been Lindbergh’s former commanding officer in the Army Air Service, and Leininger used that connection to gift Lindbergh a Franklin sedan while the aviator was in England, lucky him, after which Leininger also hired Lindbergh to promote the Franklin.

Lindberg with Franklin Airman Sedan. Note the false radiator. image courtesy AACA library.

Franklin Steps Out

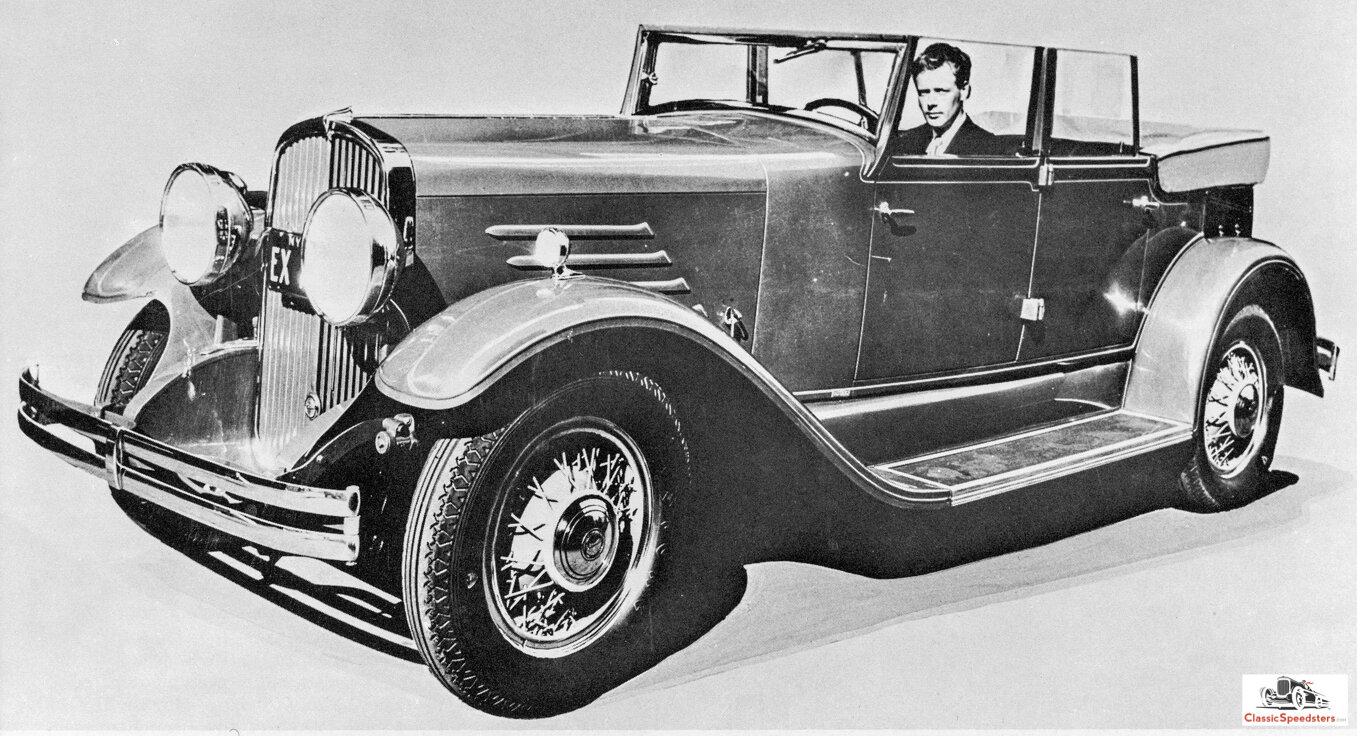

Raymond Dietrich penned the Model 137 four-passenger Speedster model for Franklin in 1929 that would also be part of the Airman series.

Raymond Dietrich's Franklin Speedster pen-and-ink drawing. Image courtesy H.H. Franklin Club library.

Sporting a 132-inch wheelbase, fabric top, raked windshield, lowered body, and narrowed hips, the Dietrich Speedster had a low, racy look to it. Its 67 horsepower engine displaced 274 cubic inches and featured a high compression aluminum head, aluminum crankcase and lightweight rotating assembly.

1928 Franklin Airman Engine. The false radiator would provide a frontal air supply which, in turn, would be blown onto the cylinders via the front-mounted fan to effect cooling. Image courtesy H.H. Franklin Club library.

With a four-speed transmission and a high ratio rear differential, it spoke of speed. All told, this car was meant to cruise four passengers comfortably at high velocity; 100 miles per hour was attainable.

Dietrich Speedsters were considered four-seater sports cars by Franklin, and their marketing materials pushed that. The initial press release announced

A new Franklin enclosed sports car…Designed and built by Dietrich, it translates into slanting lines and long horizontals the form and beauty of the Age of Speed. Here is a car for Youth and sophisticated America…

Dietrich Speedsters were lifestyle statements, differentiating each demographic by subtle color arrangements rather than the modern practice of horsepower options or special accessories. Different colors were used to target the “rugged outdoor sportsman”, the “thoroughly modern woman”, or “a smart new couple in their smart new life together.” Overall, ads for Dietrich Speedsters focused on the younger, more modern, free-thinking set.

Dietrich Speedsters were offered in a fixed hardtop or fabric convertible. By 1931, the six cylinder produced 100 horsepower, and in 1932 Speedsters were also optioned with the new V-12 engine from the custom body department. Of the 154,000 Franklins that were manufactured from 1902 until 1934, approximately 2000 were Speedsters, and one historian wrote that about 17 were V-12s. However, no corroborating data exists on whether any were fitted with this engine.

Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and Frank Hawks all loved fast machines, which is why these aviators were hired by Leininger to promote the speedy Dietrich Speedster and other models of the Franklin Airman series.

Lindbergh in 1929 Franklin Dietrich Speedster, which came in convertible or hardtop. Image courtesy H.H. Franklin Club library.

Endorsements by these au courant aviation greats, along with Cannon Ball Baker’s record-setting endurance achievements in a Franklin that he affectionately called “that old waffle-iron,” sent a strong performance message to the public. Franklin sold 14,432 cars in 1929, its most ever.

Next episode we’ll conclude this theme of variants of the classic speedster concept with a look at another venerable company. By the way, if you are curious about the history of Kissel and Franklin, both car companies and their speedsters inform chapters in my book.

Speaking of which—Good News! I will also have more developments to share regarding my upcoming book on classic speedsters, and hope to reveal our choice of book cover with you as well. It’s been quite a journey getting to the point of publishing it, and so I am thinking of writing a separate blog on that trek. Believe me—it’s been a long one!

See you then…